AGNÈS THURNAUER: Land and Language

1st floor of KHB

Opening:

December 7th 2016

from 6 p.m. until 8 p.m.

Duration:

December 8th 2016 – January 29th 2017

Venue:

Kunsthalle LAB

In terms of the exhibition communication to the outside world, given that its components, by far not non-essential, is the attractive visual representation of works, stands a good chance of overcoming the natural barrier between the closed space of the presentation and the public exterior. At the same time – also in connection with the venue of the exhibition (Kunsthalle LAB Bratislava) and due to the character of the selected works (as a specific section of the author’s creative work), it is a relatively freely, definitely not intentionally set-up exhibition in the LAB representing the kind of art which could also be assigned the attributes of the area reacting to the issues of feminism as well as gender art [1].

Although in case of the given segment of works, contrary to the character of works presented at the above-mentioned exhibition where they individually communicated the contents subjectively reacting to the theme of the current view of gender application, (also from the point of view of male – artists), Agnès Thurnauer touches upon the „globalized“ topic - the disparity of women and men represented in the history of fine arts.

The primary decoding of the works – a series of „buttons“ with names of, as if, their female „opposites“, or variations or transcripts of male artists names / personalities of 20th century art history, really refers to the discourse, my times theoretically articulated, of the so-called writing of art history through works created by men, or through the male optics[2], which is, also in case of the presented works of the female artist, their fundamental base. The objects have an expressly minimized morphology – a simple round shape of an oversized lens emphasizing the precise elaboration leading to form purism, which, though, in this case is more statement expressive than any other form and by its charging impact it can also be close to the strategy of an advertisement slogan which usually carries a compressed contents to be communicated.

An important aspect is represented also by the form itself – a round suspended object as an allusion of a portrait, in this case rather substituting than representing a fictitious figure: e.g. Marcelle Duchamp, Annie Warhol, Joséphine Beuys, Jacqueline Pollock. The given name thus becomes a symbol of a non-existent reality in which, behind the name of a figure, there is also a coded reference to the artworks on which we could – hypothetically – write a history of art other than the one we know.

This version of the portrait in which the creation of an opposite against the generally known reality defying its basic function is integrated, since it symbolically presents something what that has never been before, is the basic construction component of this series and really it can also be the basis for an interpretation from the perspective of the institutional critique or that of an artistic operation. An example of such an approach is her previous exhibition Bien faite, mal faite, pas faite in Gent[3] where the artist applied the names of fictitious female artists as certain „alter egos“ of not only reputed artists, but also of some men from the history of culture and philosophy, on the walls within the building interior. The present collection Portraits Grandeur Nature nevertheless brings along a significant superstructure – in the perception of Agnès Thurnauer it is not only an effort to create exactly formulated (based on the name typology) female opposites in the sense of critical reassessment of art history writing, but also a deliberate blurring of gender reading of this history , namely by means of fiction created in this way, the sources of which we can however read reliably.

The question posed by the artist through this series (and the collection presented at the exhibition was actually based on it too), is also to what extent the gender aspect is important in perceiving the painting (art) by viewers. Here, a significant role is played by the present principle of (non) depiction – the objects of the series of portraits are a manifestation of a symbolic substitution of a fictitious reality rather than traditional painting formats through a relevant narration, whose final shape and contents, according to the artist are also considerably affected by the participation of the viewer through his/her perception. Thus fine arts – painting, which represents the realm of her work, for her becomes principally the aspect determining their mutual relationship and primarily does not have to be subordinate to categorization/interpretation on the basis of gender criteria. For this reason, too – in a certain subversive manner – the collection Portraits Grandeur Nature also provides space for the version of the male „opposite“ of Louise Bourgeouis’s name in the form of Louis Bourgeouis.

The execution of the XX story (since 2003) is a long-term „work in progress “, which derives from the basis similar to the portrait series. One of its versions includes a big canvas format consisting of the female name forms of some well-known artists of art history from the 12th to 20th centuries implemented as a drawing. It is actually the first work whereby the artist began to react to the gender issue in art history gradually developing this line in several media. Besides the present „buttons“ it continuously appears in the paintings and projects, which are based on text and objects. As a certain, initially formal pendant to this work, in terms of narration or communication by means of text/language, there is the series of „grids“ of alphabet letters Matrice/Sol (2014), shaped in a reverse order – by the hollow volume whereby the artist demonstrates the fact that art is first of all a matter of reading, interpretation and language and these components are in constant and variable movement and they are always generated into a new form.

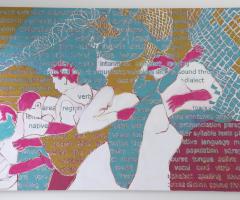

One of the recent artist’s works, the painting Land and Language (2016), to a certain extent, represents a logical outcome of her long-term interest in language and art where the text is an important tool of not only creation, but also communication and interpretation. It demonstrates another sphere of her interest dedicated to the topic of migration, not only in the sense of physical, but mainly mental activity. She deals with the issue of how we are able to „migrate“ from one language to another, what limits and restrictions this migration brings along to our consciousness, and what its consequences may be.

Mira Sikorová-Putišová

Exhibition curator

[1] This topic was addressed by the exhibition Fem(inist) Fatale in Kunsthalle LAB Bratislava (17.7.2015 – 6.9.2015).

[2] It mainly concerns the essay by Linda Nochlin Why There Have Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) as well as the publication by Roszika Parker and Griselda Pollock Old Mistress: Women, Art and Ideology (1981). More: Foster, Hal – Krauss, Rosalind – Bois, Yve-Alain – Buchloch, Benjamin H. D.: Umění po roce 1900. Modernizmus, antimodernizmus, postmodernizmus. Praha: Slovart, 2007, p. 572.

[3] Bien faite, mal faite, pas faite (Well done, badly done, not done), S.M.A.K. Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst Gent, 27.1. – 20.5.2007.

- - - - -

- - - - -

Co-organizer of the exhibition: French Institute in Slovakia, Embassy of Switzerland in Slovakia

Exhibition partner: Vetropack

///

Dans cette exposition de l’artiste franco-suisse Agnès Thurnauer, domine la série qu’elle avait déjà présentée au Centre Pompidou à Paris, les Portraits Grandeur Nature (2007 – 2009), grands badges ronds et colorés. De par cette première présence visuelle attrayante, l’ exposition franchit allègrement la frontière vitrée entre l’espace fermé où elle est située et l’espace public extérieur. Par ailleurs – toujours par rapport au lieu de l’exposition (Kunsthalle LAB Bratislava) –au regard de la nature de la série choisie (en tant que représentative de l'œuvre de l’artiste), cette exposition s’inscrit naturellement et de manière non intentionnelle, dans une série d’expositions artistiques organisées à LAB qui traitent de la problématique du féminisme et de la question du genre[1]. Cet aperçu propose toutefois, contrairement aux œuvres présentées lors de l’exposition qui abordait, de manière subjective, la problématique de l’application des points de vue par genre dans la société d’aujourd’hui (aussi bien le point de vue des hommes – artistes), un thème « mondial » : l’inégalité concernant la représentation des femmes et des hommes dans l’histoire des arts plastiques.

A l’origine il y a le décodage des œuvres – d'une série « de badges » avec des prénoms masculins « féminisés » ou avec des variantes, voire transcriptions des prénoms des hommes artistes et figures centrales de l’art du XXème siècle. Agnès Thurnauer fait ainsi référence à un discours théorique à maintes fois répété et repris, qui est au cœur de l'œuvre présentée, celui de l’histoire de l’art écrite par le biais des œuvres réalisées par les hommes[2], soit dans une optique masculine. A la morphologie expressément minimale, les objets ont une forme ronde de lentille surdimensionnée, l’accent est mis sur l’élaboration précise proche du purisme de la forme, qui est toutefois plus explicite que toute autre forme et qui accroche tel un slogan publicitaire condensant le message à communiquer. La forme même en est un autre élément important : l’objet rond suspendu fait allusion au portrait qui substitue plutôt que représente un personnage fictif comme par exemple Marcelle Duchamp, Annie Warhol, Joséphine Beuys, Jacqueline Pollock. Le nom affiché devient ainsi un symbole d’une réalité inexistante et dernière ce nom d’un personnage se cache un message, lui aussi codé, qui renvoie aux œuvres d’arts plastiques, pouvant servir de base pour écrire, de manière bien hypothétique, une histoire de l’art différente de celle que l’on connaît aujourd'hui.

Une telle version d'un portrait où la forme opposée intègre la réalité généralement connue, tout en contestant sa fonction principale, car symboliquement ce portrait représente ce qui n’avait jamais existé, constitue un élément central de cette série et peut servir de point de départ pour une interprétation sur le plan d'une critique institutionnelle ou d'une critique du fonctionnement artistique. L’exposition antérieure de l’artiste Bien faite, mal faite, pas faite qui a eu lieu à Gand met en exergue cette approche[3] : à l'intérieur d'un musée Agnès Thurnauer introduit sur les murs les noms des femmes fictives – plasticiennes, tels les alter ego non seulement des hommes artistes connus mais aussi des grandes figures de la culture et de la philosophie. Dans cette perspective s'inscrit également la présente collection Portraits Grandeur Nature dans laquelle, selon Agnès Thurnauer, il ne s’agit pas seulement de créer exactement (sur la base de la typologie des noms) des formes opposées féminines dans le sens de la réévaluation critique de l’histoire de l’art mais aussi d'obscurcir la lecture de genre dans l’histoire de l’art et ce en inventant une fiction dont on peut dégager des grandes lignes.

A travers cette série, l’artiste soulève également, la question de savoir dans quel mesure le sexe (le genre) influence la perception de la peinture (de l’art) par le spectateur (la collection présentée à l’exposition a d’ailleurs été créée à cet effet). Le principe de (non-) représentation y joue un rôle important – objets de la série de portraits expriment davantage une réalité fictive qu'une narration, racontée à travers des formats traditionnels de la peinture, dont le résultat et le fond sont largement influencés par la perception du spectateur. Les arts plastiques, notamment la peinture qui est au cœur de l’œuvre d’Agnès Thurnauer, deviennent pour l’artiste un aspect qui détermine le lien entre eux et qui ne contribue pas spécialement à la catégorisation/interprétation basée sur les critères de genre. Aussi, de manière quelque peu subversive, dans la collection Portraits Grandeur Nature, l’artiste masculinise également le nom de Louise Bourgeois qui devient Louis Bourgeois.

« XX story » (réalisé depuis 2003) est un « projet en cours » qui repose sur le même principe que la série des portraits. L’un des travaux réalisés dans le cadre de ce projet est la grande toile sur laquelle sont dessinées les formes féminisées des noms des artistes de renom du XIIème au XXème siècle. Pour la première fois, une artiste réagit à la question du genre dans l’Histoire de l’art et dans cette optique elle poursuit progressivement son travail tout en exploitant plusieurs média. En plus des « badges », la peinture et les projets interconnectant le texte et les objets sont aussi représentés. La série de moules de lettres de l’alphabet Matrice/Sol (2014) apparaît comme le pendant, de prime abord formel, de cette œuvre, au sens de la narration ou bien de la communication à travers le texte/le langage : lettres en volume creux créent de manière réversible une matrice par quoi l’artiste démontre que l’art est tout d’abord une question de lecture, d'interprétation et de langage, ces éléments sont inconstants et instables et changent sans cesse de forme.

L’une des plus récentes œuvres de l’artiste, le tableau Land and Language (2016), est d'une certaine manière un aboutissement logique de l’intérêt de l’artiste pour le langage pictural. Entre le langage et l’art, le texte paraît un important outil non seulement de la création mais aussi de la communication et de l’interprétation. Agnès Thurnauer ouvre ainsi un autre champ d’intérêt, celui de la migration, perçue non seulement comme une performance physique mais aussi mentale. Elle s'interroge sur notre façon de « migrer » d'un langage à l’autre de même que sur les conséquences de ces limites et de ces restrictions sur notre conscience.

Mira Sikorová-Putišová

Commissaire de l’exposition

[1] L’exposition intitulée Fem(inist) Fatale qui a eu lieu à Kunsthalle LAB Bratislava (17/07/2015 – 06/09/2015) a été consacrée à ce thème.

[2] Il s’agit notamment de l’essai de Linda Nochlin Why There Have Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) et de la publication de Roszika Parker et de Griselda Pollock Old Mistress: Women, Art and Ideology (1981). En savoir plus : Foster, Hal – Krauss, Rosalind – Bois, Yve-Alain – Buchloch, Benjamin H. D. : L’art après 1900 Modernisme, antimodernisme, postmodernisme. Prague : Slovart, 2007, p. 572.

[3] Bien faite, mal faite, pas faite (Well done, badly done, not done), S.M.A.K. Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst Gand, 27/01 – 20/05/2007.